The Best Chinese Idioms to Sound Smarter

Idioms in English vs. Chinese 成語

The word “idiom” as it relates to English is actually very vague. The Oxford dictionary defines it as “A form of expression, grammatical construction, phrase, etc., used in a distinctive way in a particular language, dialect, or language variety…”. Examples of English idioms include phrases like “turn a blind eye”, “beat around the bush”, and “spill the beans”.

In Chinese, however, the word 成語 (translated as “idiom”) is generally more specific and well defined. 成語 are expressions that are typically four characters long and usually allude to or quote classical Chinese texts in order to refer to specific situations or bits of wisdom. Unlike idioms in English, it’s more common for Chinese speakers to know exactly what text their idioms come from, making them extremely rich in meaning. For this reason, 成語 are usually associated with high culture and history, and using them can make your speaking or writing sound more formal and articulate.

Essentially, English idioms like “it takes two to tango” sound informal and quirky, while Chinese 成語 have the opposite effect. Integrating some Chinese idioms into your vocabulary is essential for becoming a true master of Chinese and sounding smart!

成語故事: The Stories Behind Idioms

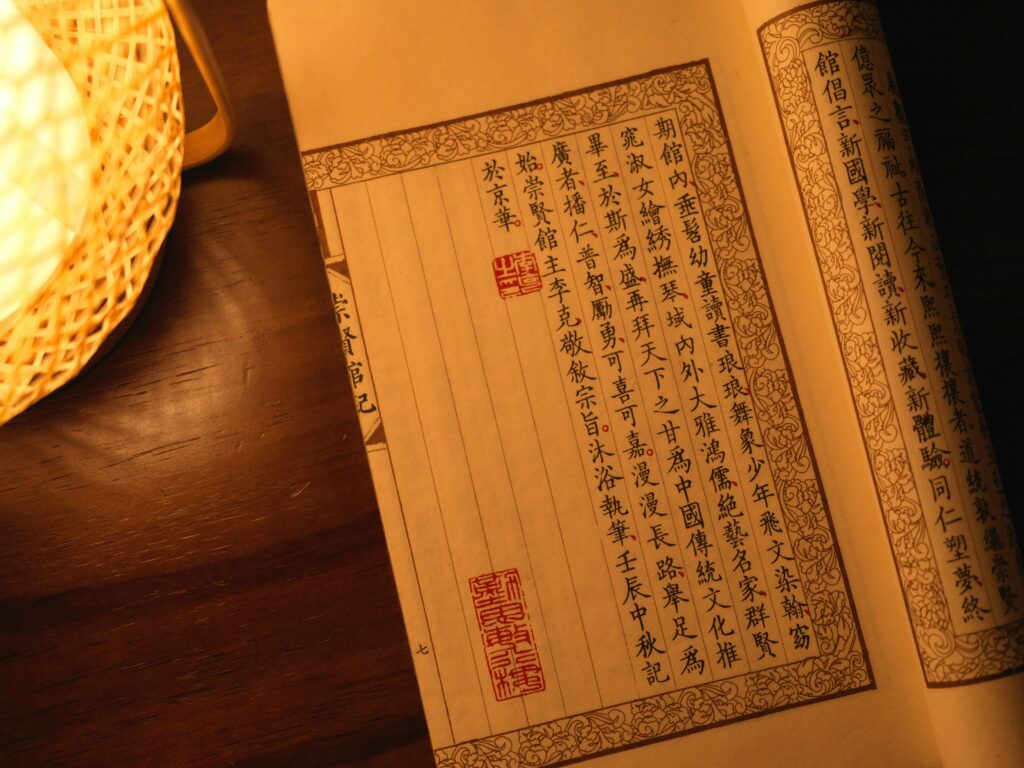

A common way that 成語 are taught in China is starting with the original text that they originate from. Learning the whole story behind a 成語 makes the meaning and the idiom itself almost impossible to forget. Here are 12 idioms that you can learn now to spice up your Chinese, along with the texts they originate from. If you’re interested in reading abridged versions of these stories tailored for language learners in Chinese, check out our Stories Behind Chinese Idioms course!

成語 from Historical Texts

Many 成語 come from historical texts and allude to the actions of specific historical figures, be it in battles, the court, or otherwise. These idioms are can make you sound well read and aware of Chinese history. They’re great for summing up complex every-day situations.

三人成虎 - “Three people make a tiger”

Text of origin: 戰國策 (Strategies of the Warring States)

This idiom refers to how rumors spread and how the truth can be distorted by false information. It can be used to describe situations where rumors begin to distort reality.

樂不思蜀 - “Too happy to miss Shu”

Text of origin: 漢晉春秋 (Chronicles of Han and Jin)

This idiom refers to Liu Shan, a famous historical figure, and how he forgot about the plight of his kingdom because he was too busy having fun somewhere else. It can be used to describe a person who loses their roots or ties to their home, and can sometimes be used to describe a particularly fun or enchanting place.

紙上談兵 - “Discussing military tactics on paper”

Text of origin: 史記 (Records of the Grand Historian)

“Discussing military tactics on paper” refers to frivolous or overly idealistic discussions that aren’t rooted in reality.

毛遂自薦 - “Mao Sui recommends himself”

Text of origin: 史記 (Records of the Grand Historian)

This idiom refers to Mao Sui, another figure from Chinese history, and how he took initiative and recommended himself for an important diplomatic position. It can be used to describe the act of recommending oneself for a role.

成語 from Philosophical Texts

Philosophy has always played an extremely important role in Chinese culture. Many 成語 quote works of philosophy to refer to complicated situations with moral implications. These are especially good for sounding smart!

塞翁失馬 - “The old man lost his horse”

Text of origin: 淮南子 (Huainanzi)

This one is difficult to understand without knowing the story behind it. In the original story, a man is unphased by the ups-and-downs he experiences in his life. It expresses the idea that “good things” and “bad things” are relative. It’s similar to the English phrase “a blessing in disguise”.

朝三暮四 - “Say three in the morning but four in the evening”

Text of origin: 莊子 (Zhuangzi)

Another abstract one from Daoist philosophy. This idiom refers to the idea that sometimes the way a situation is presented can drastically change someone’s perspective, even if nothing about it changed.

高山流水 - “High mountains and flowing water”

Text of origin: 列子 (Liezi)

This idiom alludes to a tragic tale of friendship and is used to describe an extremely deep bond.

愚公移山 - “The foolish old man moves mountains”

Text of origin: 列子 (Liezi)

This idiom comes from a folk tale where an old man decides to move a mountain. It’s used to describe acts of persistence even in the face of extreme adversity.

魚目混珠 - “To pass off fish eyes for pearls”

Text of origin: 參同契 (Cantong qi)

“Passing fish eyes for pearls” refers to mistaking something cheap for something valuable. It can be used in situations where someone is overestimating the value of something.

拔苗助長 - “Pulling shoots to help them grow”

Text of origin: 孟子 (Mengzi)

This idiom refers to the act of doing something “helpful” in a short-sighted way that actually does more harm than good. It’s usually used to describe situations where someone is so anxious to see results that they fail to act reasonably.

買櫝還珠 - “To buy a wooden box and return the pearl inside”

Text of origin: 韓非子 (Han Feizi)

This idiom comes from a story where a merchant builds a beautiful box in order to sell a pearl, only to find that customers are more interested in the box than the pearl itself. It’s used to describe situations where people are more interested in the marketing or presentation of something rather than the actual thing being presented.

刻舟求劍 - “To notch the boat in search of the sword”

Text of origin: 呂氏春秋 (Lüshi Chunqiu)

In this story, someone drops their sword off of a boat and into a river. They then make a notch in their boat to mark where they dropped their sword. This idiom is used to describe situations where someone’s thinking is overly rigid or unrealistic, and can emphasize that our way of thinking should reflect the reality of a situation.

Learn Culture and Language Together

成語 are a treasure trove of literary and cultural knowledge that can help you take your language and cultural knowledge to the next level and make you sound smarter! If you’d like to read the full story of these idioms while improving your reading along the way, be sure to check out our idioms course for a detailed rundown in Chinese. For more lessons designed to help you improve your Chinese through reading, be sure to visit duchinese.net/more!