What is Classical Chinese and Why is it Important?

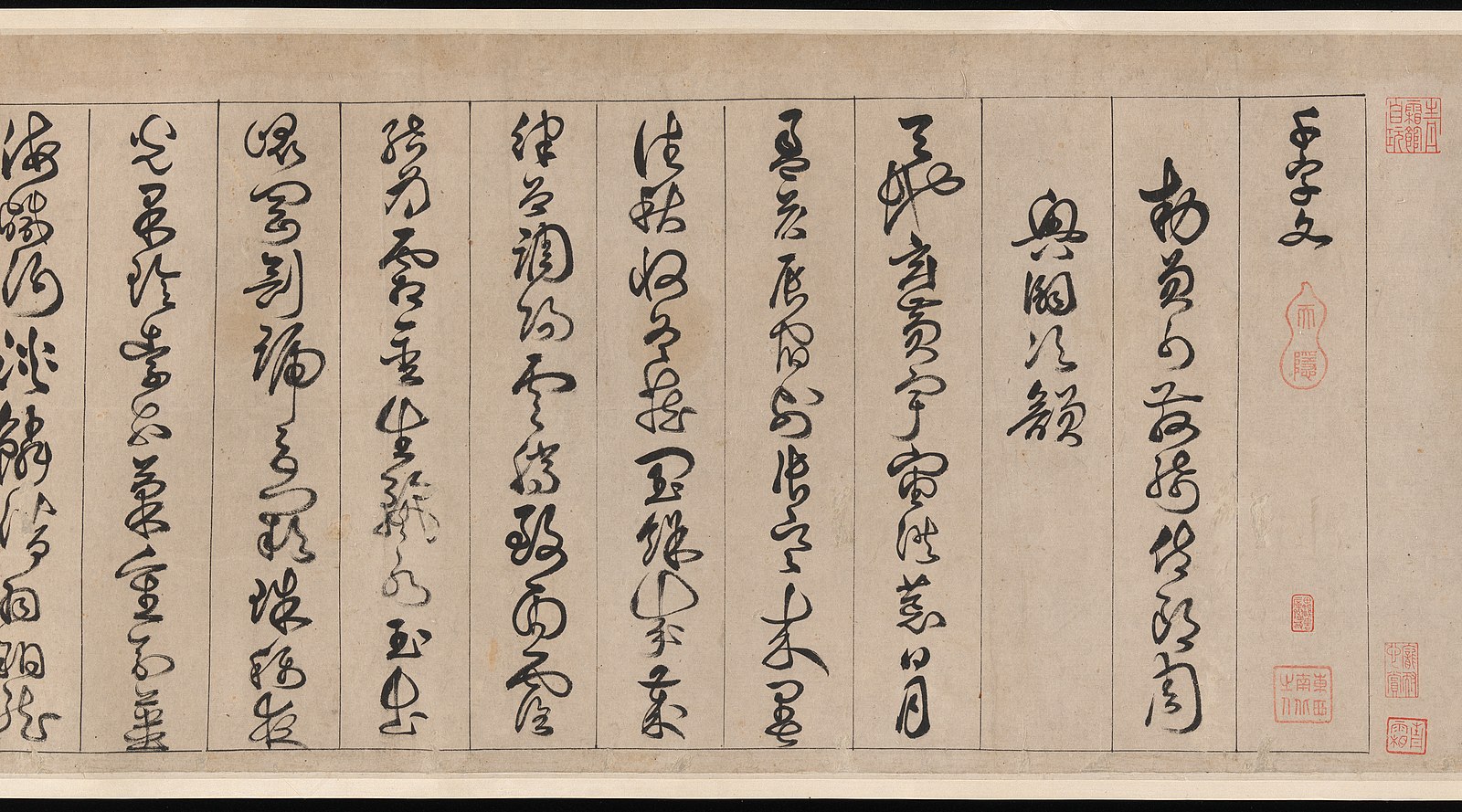

Classical Chinese, also known as literary Chinese, is a form of writing that defined writing and literature in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam for centuries, but what is it?

What is Classical Chinese?

- Classical Chinese is written with Chinese characters, which don’t explicitly tell the reader exactly how they’re pronounced

- Classical Chinese is meant to emulate the earliest Chinese texts, so it hasn’t changed much over time

- There are a multitude of dialects spoken within China, which have all been evolving over centuries

- Communicating over long distances requires a form of writing that anyone can learn to read, regardless of dialect or language spoken

To put it simply, Classical Chinese was useful as a language that anyone could learn to read and write, regardless of what dialect of Chinese (or any other language) they spoke.

While spoken language changes rapidly, Classical Chinese was intentionally left as untouched as possible, so that any person could learn and use it. It’s for this reason that many neighboring countries (Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, for example), adopted and used Classical Chinese as their written language, especially when communicating with China or each other. It’s important to note that no one has actually “spoken” classical Chinese for two thousand years. Also, Classical Chinese and “Traditional Chinese” are completely unrelated concepts! Classical Chinese is China’s ancient written language, whereas Traditional Chinese refers to Chinese characters as they existed before being simplified in the mid 20th century.

A great way to understand how Classical Chinese was used would be to look at how Latin was used in Europe to communicate between countries who spoke different languages!

When was Classical Chinese used?

Classical Chinese was used in China from the 5th century BCE until it was eventually replaced with vernacular Chinese (Chinese written the way it’s spoken) following the May 4th Movement in 1919. This gives us an impressive 2,500 year run! Japan, Korea, and Vietnam all followed suit in the early 20th century, but for hundreds of years correspondence between these nations would have all been written in Classical Chinese.

Character-istics of Classical Chinese

Classical Chinese has many characteristics which make it very distinct from Mandarin. After all, while it can be read out loud in Mandarin (or Japanese, actually) it is its own language!

Distinct particles

Classical Chinese is littered with fancy particles that serve grammatical functions. Some of the most common include:

- 之: Possessive particle or 3rd person pronoun

- 乎: Indicates a question or location

- 者: Used to indicate a class of persons or things

- 也: Used to indicate a judgment or explanation

These particles can still be found in Mandarin to some capacity, but they’re so prevalent in Classical Chinese that there’s even a word “之乎者也” which refers to literary jargon or archaisms.

See if you can spot some in this sentence!

夫子之求之也、其諸異乎人之求之與。

“His way of obtaining [it] differs from that of other people.”

-Analects of Confucius

Words are usually one character

Unlike Mandarin, which has countless words composed of two or more characters, Classical Chinese usually sticks to one. Here are some examples:

- 知道 > 知 (to know)

- 安靜 > 靜 (quiet)

- 開始 >始 (to begin)

As you can see, a lot of Mandarin words with two characters will often contain a character that might’ve been used on its own to mean the same thing in Classical Chinese, but this isn’t always the case!

Concise and to the point

Interestingly enough, Classical Chinese can be difficult to understand precisely because it uses words so sparingly. When translated directly into English word by word, it can read almost “caveman-like”. What’s funny is that Classical Chinese is often translated into very wordy English to capture the literary feel of it, so English translations often end up significantly longer and more complicated than the original.

千里之行始於足下。

| Thousand | mile | of | journey | begin | at | foot | down | .

“A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.”

-Dao De Jing

As you can see, the English translation for this famous aphorism almost has to work harder than the original to make it “sound fancy”. This is a fun quirk of Classical Chinese, but this very pared down and direct style of writing can actually be incredibly difficult to understand when the subject matter gets more complicated.

Classical Chinese in the modern world

Nowadays, Classical Chinese is still taught in schools in China and Japan and is considered an important part of education. On top of its cultural and literary value, Classical Chinese is also baked into many sayings, idioms, and expressions, which are often quotes from important pieces of literature and used in daily life. In the case of Mandarin, more technical or literary writing also tends to lean more towards Classical Chinese grammar and vocabulary. You can think of the “technicality” scale of Chinese as a slider between colloquial, casual Chinese and rigid Classical Chinese:

這個事情真沒意思。

“This stuff is boring.”

這件事沒有意義。

“This matter is meaningless.”

此事毫無意義。

“This affair is veritably bereft of meaning.”

Note how in order to capture the “classical-ness” of the formal writing, the English gets longer and more verbose, while the Chinese gets shorter and more concise.

Value of Classical Chinese

Essentially, pretty much anything put to writing in China before the early 20th century was written in Classical Chinese. That means that over 2000 years of poetry, literature, stories, history, and correspondence with other East Asian countries has been written down in one language. Classical Chinese might be challenging to learn, but when compared to Europe’s convoluted linguistic history, it’s truly amazing how much this literary language has to offer. Learners of Classical Chinese will be able to read letters written from Ghengis Khan to the Emperor of Japan, ancient books of divination, works of profound philosophy, calligraphy, and journals written by people centuries ago–there really isn’t a more accessible window into the past than Classical Chinese.

On top of the cultural value of Classical Chinese, its tendency to rear its head in technical Chinese also makes it a valuable challenge for learners of Mandarin. After all, if you have some basic Classical knowhow, fancy Mandarin won’t scare you anymore!

How do I learn it?

A foundation in Mandarin is extremely important when trying to tackle Classical Chinese, especially when you consider that learning material in English is much harder to find than Mandarin resources. That being said, one good way to attack Classical Chinese is to pick a text that interests you, and find a translation in either Mandarin or your native language. Usually, Classical Chinese is much easier to decipher when you already know what it means. Once you know the meaning of a sentence, going in and picking it apart to understand what’s happening can be a fun and rewarding challenge!

Pave the way to classical mastery!

While we don’t offer texts written in Classical Chinese, you can check out Outlier Linguistic’s Intro to Literary/Classical Chinese course. If you are interested in Chinese literature, dive into the adaptations of ancient Chinese stories on Du Chinese. Why not read our take on Mulan, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, or other important pieces of Chinese literature!